who gets to do the right thing?

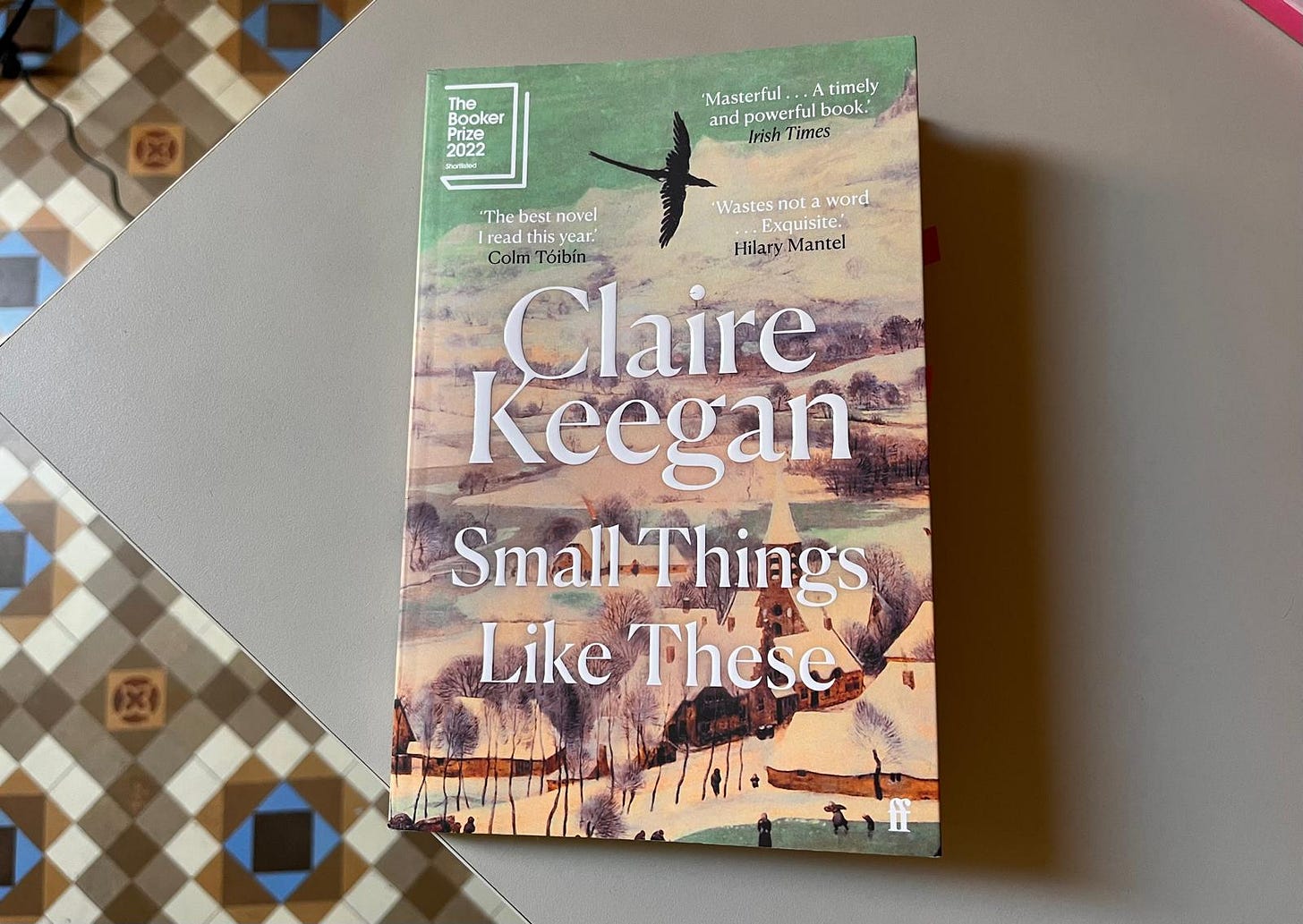

claire keegan's Small Things Like These

In a way, Claire Keegan’s Small Things Like These is about how all the feelings you’ve repressed throughout the year will inevitably come back to haunt you in the weeks before Christmas, when work eases and free time, with all its tangents, begins to rear its ugly head. You ask yourself questions like: what am I doing with my life; is my past consistent with my present; what will my future look like, if I keep doing what I’m doing?

And then, the kicker: will acting on what I consider to be the morally good thing lead to relief—or grief? If inaction will produce the latter regardless, does it matter? And how silly, really, to consider any of it binary, when I know that most decisions I take will result in a combination of relief and grief. Who bears it, if not just me?

These are the things—not small at all!—that I considered on Friday afternoon as I was reading Keegan’s novella, and then again on Friday night as I was watching its new film adaptation that is, it should be said, a gorgeous 98 minutes long and rather faithful to the text.

Apologies, I guess, in that this will involve my thoughts on both the novella and the film, although mainly the former. Some spoilers, although not really. I find that the enjoyment from this book, as from most good ones, comes from reading it, not finding out what happens.

*

Set in Ireland in 1985, Small Things Like These is a story about Bill Furlong, a coalman with a wife and five daughters, who in the days leading up to Christmas feels increasingly burdened by the weight of his memories and his conscience as he repeatedly witnesses first-hand the effects of the Catholic Church’s control over his small, struggling town. The focus of Furlong’s attention, and the novella’s moral conflict, is the Magdalene laundry, also known as a Mother and Baby Home, to which he delivers coal.

*

According to the Inter-departmental Committee to establish the facts of State involvement with the Magdalene Laundries, over 10,000 girls and women were detained in these homes between 1922 and 1996, when the last laundry was closed.1

Who were the girls and women sent to the Catholic-run laundries? Sex workers, unwed mothers, orphans, victims of rape, incest, and abuse, and, more generally, those who did not conform to the time’s moral norms.2

The nuns who ran these homes did not only mistreat the women and girls sent to them—often against their will—, they also turned them into unpaid laborers—for the church, for businesses, and for the state.

Once inside the convents, girls and women were imprisoned behind locked doors, barred or unreachable windows and high walls (oftentimes with broken glass cemented at the apex). They were usually given no information as to when or whether they would be released. Upon entry, their names were often changed and they were given an identification number. Many women recall being instructed not to speak about their home-place or family. Their hair was cut and their clothes were taken away and replaced with a drab uniform. A rule of silence was imposed at almost all times in Magdalene Laundries and, in many women’s experiences, friendships were forbidden. Correspondence with the outside was often intercepted or forbidden. Visits by friends or family were not encouraged and were often monitored when they did occur.3

In 2013, twenty years following the finding of a mass grave in a Dublin Magdalene, the state formally apologized for its role in the continuance of the institution.

*

Places like the Magdalene laundries are open secrets. Pointless to argue or pretend otherwise, so I won’t. People know they exist, they know there is mistreatment and abuse afoot, and they know, even if they don’t like to admit it, that it is morally wrong. So the question then becomes: what is the cost of speaking out against it? Surely there is a high one, otherwise the protests would be overt and far-reaching. And the cost in this case, of course, is punishment and alienation by the Catholic Church, which in 1985 still controls quite a bit of Irish culture and society. It is the nuns, for instance, who also run the only all-girls school in town. And Furlong, let us remember, has five daughters.

But Furlong’s mother, long dead, was an unwed mother, too. One who, by some twist of fate and an employer’s kindness, was kept away from such an institution.

What, then, is a man to do? Who carries the sacrifice of taking the moral high road? To what extent should such cost act as a deterrent? Where does the guilt go?

These are uncomfortable questions, but it is something I’ve been thinking a lot about over the last few years. I have no children, which I think has made it a lot easier for me to call certain things out, knowing that in all likelihood, the only one facing the repercussions for my actions will be me.4

Indeed, in an interview with The Booker Prize, Keegan expressed slight frustration with some readers’ interpretation of Furlong.

I know some readers see it as a story of a simply heroic character. I’m not saying that my character isn’t heroic – but I see Furlong as a self-destructive man and that this is the account of his breaking down. He’s coming into middle age, suffering an identity crisis, doesn’t know who his father is, and he’s also coming to terms with the fact that he was bullied at school. And his workaholism, which until now has kept the past at bay, is wearing thin.

The first time Bill Furlong sees the young woman locked in the coal shed of the Magdalene, he takes her back to the convent. He feels guilty about it, to be sure, agonizes over it, but he does take her back inside. The Mother Superior puts on a show for him: she manipulates the girl into confessing that it was her fellow penitents who left her in the shed, and she lightly threatens Furlong, first diminishing him by calling him “Billy” and then reminding him that the spots at the school are limited, she sure hopes there’ll be space for his girls.5 Finally, she gives him what we are to understand is an unusually generous Christmas bonus.6

When he at last leaves the convent and asks her directly, Furlong discovers the girl’s name is Sarah. Just like his mother’s.

What follows, as Keegan noted, is a breakdown.

Furlong can’t stop thinking of his own upbringing. He was bullied, yes, but at least he’d had a childhood and at least he’d known his mother—hadn’t been given away, without her consent, in a parody of Christian benevolence. He thinks about his daughters, three of whom still need to go through school. But what if his mother’s employer Mrs. Wilson, as he tells his wife Eileen, had been selfish, too, and in her rush to follow the unspoken rules, denied his mother a home and a job after she got pregnant out of wedlock? Shouldn’t he follow her example and, in his mother’s memory, do something for this girl in the Magdalene?7 Can he live with himself if he doesn’t?

Until the very last page and even beyond, we perceive this ongoing tension in Furlong’s thoughts and actions: a fight between the rules he is expected to follow and the sense of morality he cannot seem to ignore. The knowledge that staying silent, doing nothing, will ruin him and his sense of self, but that taking action might ruin his family. What difference—what small thing—can one person make?

We are so often presented with a rosy view of morality—the idea that doing the right thing may be hard, yes, but in a sort of intangible way. Something vague about bravery and swimming against the current. There’s less said about the specifics, the ones that are felt, sharply: the jobs lost, the relationships sacrificed, the marginalization, the resentment from loved ones. That’s why, of course, the collective is necessary—hard things are less so when they’re done together.

I don’t think it’s helpful to hide the ball on this. Often, doing the right thing in isolation is difficult, especially when everyone around you is playing by the rules, and especially when you’re not acting from a position of financial strength.8 It is what Keegan explores so masterfully here: why and how is it that open secrets are allowed to withstand for so long? What does it take for the dam to break?

*

Woven through Keegan’s novella is luck as a driving factor in everyone’s storylines.

It seemed both proper and at the same time deeply unfair that so much of life was left to chance.9

It was chance that allowed Furlong’s mother to keep him, just as it was chance that sent so many girls and women to the Magdalene. So then, Keegan seems to be asking, do we not bear a responsibility to give each other the best of ourselves—are not our fates by nature intertwined? (Some might say this is the true meaning of Christianity, but I’m no scholar.)

Reading this book when I was feeling a teensy little bit of sympathy for the Catholic Church following Pope Francis’s death was a bit of a trip, I’ll say that much. Zapped that sympathy right out of me.

*

This was my third read from Keegan; earlier this year I read Foster (2010) and back in 2023 I read her short story collection So Late in the Day (2023). I find her a fascinating, unsettling writer. Never am I transported—in mood, place, character—more than when I’m reading her sparse, almost unassuming prose.

When I finished Small Things, I posted on Instagram that if anyone knew Keegan, would they please let her know that her words make me feel like writing is both pointless and the only thing I could possibly do.

She writes about normal people living normal lives in deceivingly simple sentences that nevertheless leave me, a relatively normal person living a relatively normal life, reeling.

What would life be like, he wondered, if they were given time to think and reflect over things? Might their lives be different or much the same – or would they just lose the run of themselves?10

What is this, if not a thought we’ve all had somewhere in the back of our minds, distilled into meaning by someone who knows how?

Thank you for reading. You can find me on instagram and tiktok. The newsletter is fully supported by readers, so if you find yourself frequently enjoying these posts, please consider sharing the newsletter with a friend and/or becoming a paid subscriber.

Report of the Inter-Departmental Committee to establish the facts of State involvement with the Magdalen Laundries — See Chapter 8 for statistical findings.

Ireland’s Magdalene Laundries: Confronting a history not yet in the past (O'Rourke, Maeve and Smith, James M., 2016). This paper from the University of Galway is very well done and provided me with a lot of context; I encourage you to read it.

If I did have children, maybe I’d think that with my silence, they would later join me in bearing the weight of my cowardice … I don’t know.

I just know there are some folks out there who’ll be like “wait that was not clear, I think it’s up for interpretation whether she was locked by the nuns or by the girls,” and let me tell you right now: it is not up for interpretation. It is clear.

This scene, which is excellent in the novella in showing the part of him that does want to fight back, is a little less excellent in the film. In the former, Furlong goes toe-to-toe with the nun, refusing to leave her study until he’s ready to do so. He’s unpredictable; makes her sweat. In the film, he’s not as bold, cowering a bit more obviously under her presence. It’s not a choice that strengthens the narrative, I think.

A critical detail, of course, is that Mrs. Wilson was a wealthy woman and a Protestant. As Eileen reminds Bill, she was much less beholden to the rules than they—and most members of their community—are.

I am speaking, very specifically, about average private citizens here. If any politicians and elected representatives are reading this: I am not talking about you—your bravery should be built into your platform.

Small Things Like These, 55.

Small Things Like These, 19.

I loved this book. As much as I can love something that unsettled me so. Agree with your assessment of the exchange between Bill and the Mother Superior. It is a great piece of writing (when bill places his feet up on the grate!) and certainly was weakened in film adaptation.

Have a listen to this interview with Claire Keegan where she talks about some of her favourite songs as they relate to her life, on Irish radio. Absolutely fascinating woman.

https://www.rte.ie/radio/radio1/clips/22506843/